The use of expert systems seemed to me to be ideal for application within Columbia. As some of Columbia's expert in many fields would be retiring or have retired, it seemed to be a huge waste of valuable information. All you needed to build an expert system is:

- Expert - the person who currently has the knowledge.

- Knowledge Engineer, one who knows how to build an expert system.

- Expert System Tool, a program to help build the system.

- Time - a valuable commodity

I began to read all I could find on the subject and even requested books be purchased by the Research Librarian. When I was up-to-speed on the subject, I approached John Van Dyke with the idea of testing the concept. He agreed that it sounded good and, together, we worked out a plan. John would talk to friends in the Charleston, West Virginia office for a potential expert while I would attend an expert system school to learn more.

I attended a workshop given by Control Data May 6-8, 1987 on "Knowledge Engineering for Expert Systems". John got the authorization for me to work with a young engineer, Howard Murphy, who was an expert in the maintenance of glycol dehydration plants, a system that removes water from natural gas during processing and transportation. Mr. Murphy was based in Charleston, West Virginia, so I would be traveling quite a bit during the project.

I attended a workshop given by Control Data May 6-8, 1987 on "Knowledge Engineering for Expert Systems". John got the authorization for me to work with a young engineer, Howard Murphy, who was an expert in the maintenance of glycol dehydration plants, a system that removes water from natural gas during processing and transportation. Mr. Murphy was based in Charleston, West Virginia, so I would be traveling quite a bit during the project.

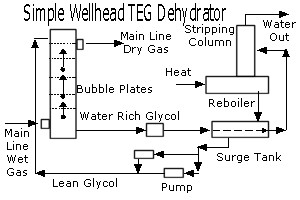

The dehydrator is pretty simple:

- Main line "wet" natural gas comes into the bottom of the Bubble plate column.

- The gas bubbles up through the glycol that is being pumped into the top of the column. Glycol "grabs" the water in the gas.

- The now gas "dry" flows out of the top of the Bubble plate column.

- The water rich glycol is taken out of the bottom of the Bubble Plate column and run through a filter on the way to the surge or storage tank.

- The "wet" glycol then goes to the top of the Stripping Column where it flows downward and the water is driven out my the heat from the reboiler.

- The dry glycol goes back through the surge tank in another piping system to cool off.

- The glycol is then pumped back to the top of the Bubble Plates where the process starts all over again.

I looked at several expert system and finally decided on one called RULEMASTER, which cost about $2,000 and ran on a PC. Yes, by this time, the later 1980s, we had personal computers. In fact, the PC I had was connected to the IBM main frame so I could work on either system.

I talked with Howard and learned his method for diagnosing a problem. I made a flow chart of his decision making and then put the logic into RULEMASTER. Unfortunately, about 2/3 of the way through his knowledge, RULEMASTER ran out of memory for constructions the rules. Therefore, I chose to continue the project using BASICA on my PC. This meant developing my own rules and flow chart for the process but, after a month or so, I got it working and it performed beautifully. The project was a success and the expert system could be placed on a 5 1/4' floppy disk and used anywhere a PC was available. Everyone thought the system was outstanding. One of my successes at Columbia. The final report is about 1" thick and contains the complete BASICA program listing.