When John and I approached out Distribution executives with the suggestion they all feared that their customers would all turn their thermostats back up over a short period of time in the morning, thus causing a serious supply problem in the system and a wide spread lose of service. This lost of service would cause the company service personnel to have to go to the houses and re-light the pilot lights of the furnaces, which would greatly increase expenses. Thus, the idea of encouraging their customers to use night setback was rejected.

Both John and I knew that people don't all get up at the same time and, thus, would not be turning up their thermostats at the same time, which was the great fear of the Distribution company. But how to convince them they were wrong?

John gave me the task of determining the effect on night setback on distribution systems. There were, at that time (1975), some gas system transient response computer programs that could predict the reaction an increase in demand on large diameter pipeline systems but they had never been used on small diameter system.

A computer transient program, GASS (GAS Unsteady State) developed by Stoner Associates, Carlisle was selected. Three typical small low pressure distribution systems in Pennsylvania were selected for study: Berlin, 372 customers, Mooncrest, 449 customers, and Fern Way, 715 customers. The simulations showed that the sudden increase in loads (demand for gas caused by the furnaces turning on) cause an instantaneous pressure reduction in the system.

So, what would or is happening on a distribution network now? We had to look at three independent variables:

- Furnace sizing and cycle time.

- Percentage of customer practicing night setback.

- Distribution of morning turn-up of thermostats.

The percentage of customer practicing night setback could be varied from 0% to 100% to determine the effect. The distribution of morning turn-up would have to be determined in order for the analysis to be completed.

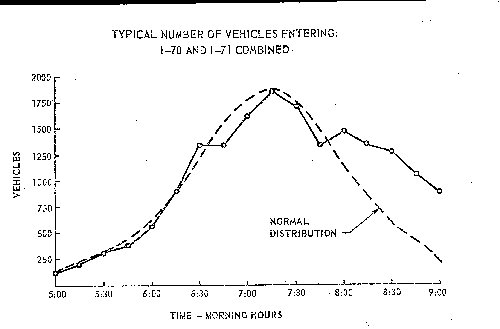

I chose three parameters that could be easily determined to model the distribution of morning turn-up, the demand for (a) water, (b) electricity and (c) the number of cars entering the freeway in Columbus, Ohio.

I chose three parameters that could be easily determined to model the distribution of morning turn-up, the demand for (a) water, (b) electricity and (c) the number of cars entering the freeway in Columbus, Ohio.

On the left is a reproduction of one of my charts, the Typical Number Of Vehicles Entering Southbound I-71 in Columbus, Ohio. This was actual traffic count from the Department of Transportation. It was clear that the traffic count was very close to a normal disbution. In other words, people didn't all get up and drive to work in large group, i.e. they were spread out of the morning.

Similar charts were made from the data on water uses (people get up, use the shower or bath, and the toilet), and electrically consumption (lights are turned on, ranges are used). Each of these parameters showed the normal distribution of people arising in the morning.

From the data in my study it was concluded that night setback of distribution's customers, even on low pressure system, which were generally over designed, would not cause a lost of service. But the distribution company decided not to purse an advertising campaign for night setback.

Another study completed and another recommendation rejected. This was becoming all too common. But, as always, other projects arose.